INTRODUCTION: After gazing upon this dramatic photograph, you should know that this image depicts the gargantuan 803-foot German airship known as the LZ-129 Hindenburg on the fateful day of May 6, 1937. Called the “Queen of the Skies”, the Hindenburg was in 1937 the world’s biggest, fastest and most luxurious airship and it could fly 9,000 miles without the need to refuel. Above is a copy of a snapshot that is held in the Stone Harbor Museum archives and below is an enlarged copy of that same photograph.

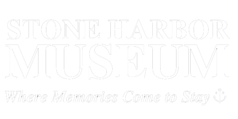

What’s so important about this photograph is it was taken by Harry S. or Jeanette Clark as the Hindenburg was lumbering slowly over Stone Harbor awaiting instructions to land at Lakehurst. Do you see the prominent town water tower in the background? One of the initial questions that should come to mind is: “What was the mighty airship Hindenburg doing flying over the South Jersey seashore resort town of Stone Harbor within an hour or so before it encountered tragedy?”

THE STORY: According to reports, the Hindenburg in making its first North Atlantic crossing of its 18 scheduled trips for its second season in 1937 was planning to land at the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey. The airship had departed Frankfurt, Germany at about 7:00 pm on May 3 and because of very strong headwinds enroute to the United States, the Hindenburg was behind schedule and the normal scheduled service of sixty hours was delayed by several hours. Obviously, there was no forewarning whatsoever that people on board this flight were destined to die. With an unblemished track record of over 25 years of zeppelin flights, there had never been any passenger injuries or fatalities. Moreover, the Hindenburg had at this point already completed 62 successful flights.

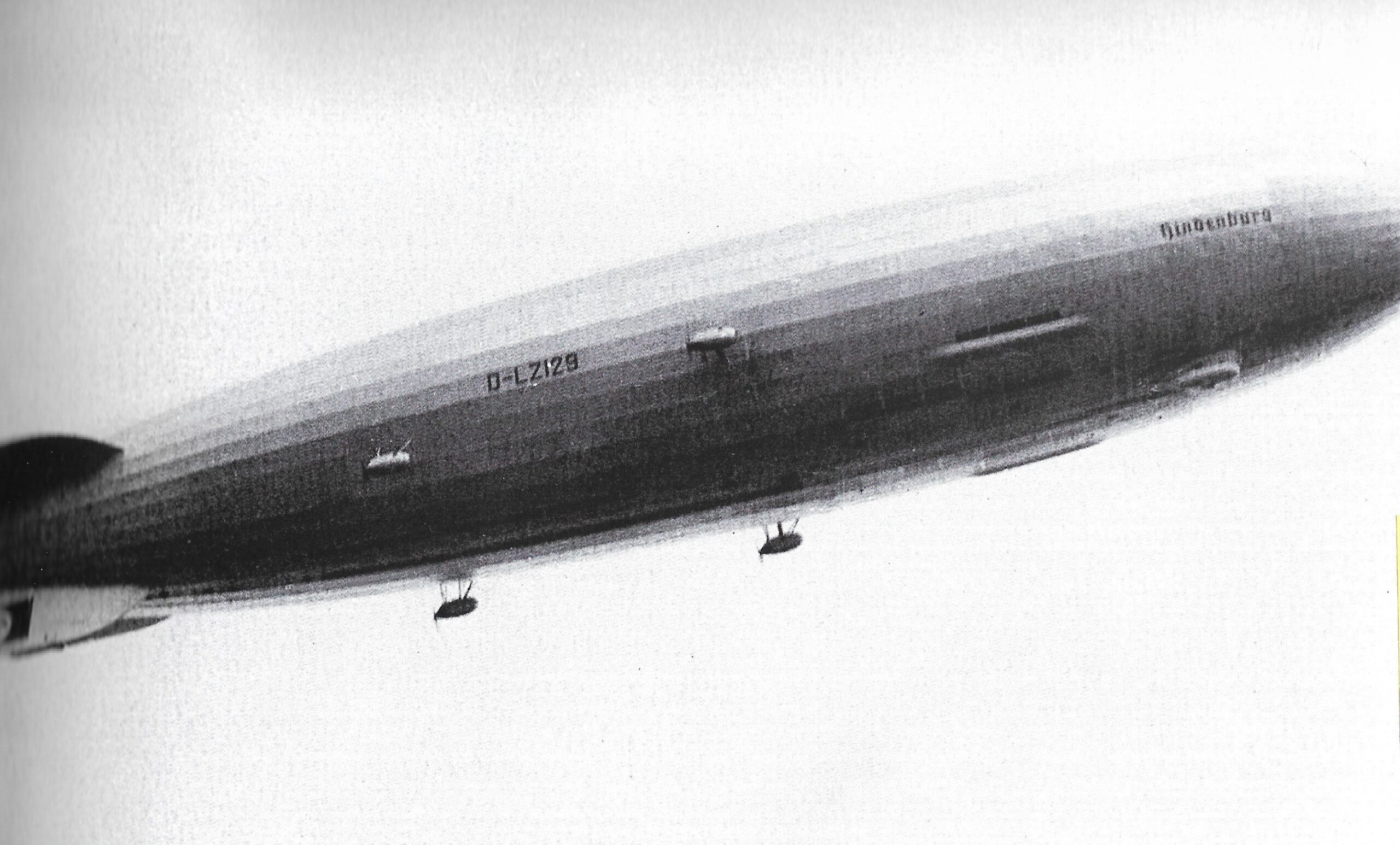

The photo above actually portrays the Hindenburg as it flies over Manhattan on May 6, 1937 just hours from its epic crash.

In addition, after overflying Boston and conducting a traditional circle of New York City, adverse weather with a thunderstorm front moved across New Jersey creating further delay in landing. The unsettled and threatening weather caused the Hindenburg to stay in the air in a holding pattern so to speak and cruising over the New Jersey Pine Barrens and along the Jersey coastline awaiting news from Lakehurst that weather conditions had changed and would permit a window of time for a safe landing. The lightning storm plagued the airfield for most of the day.

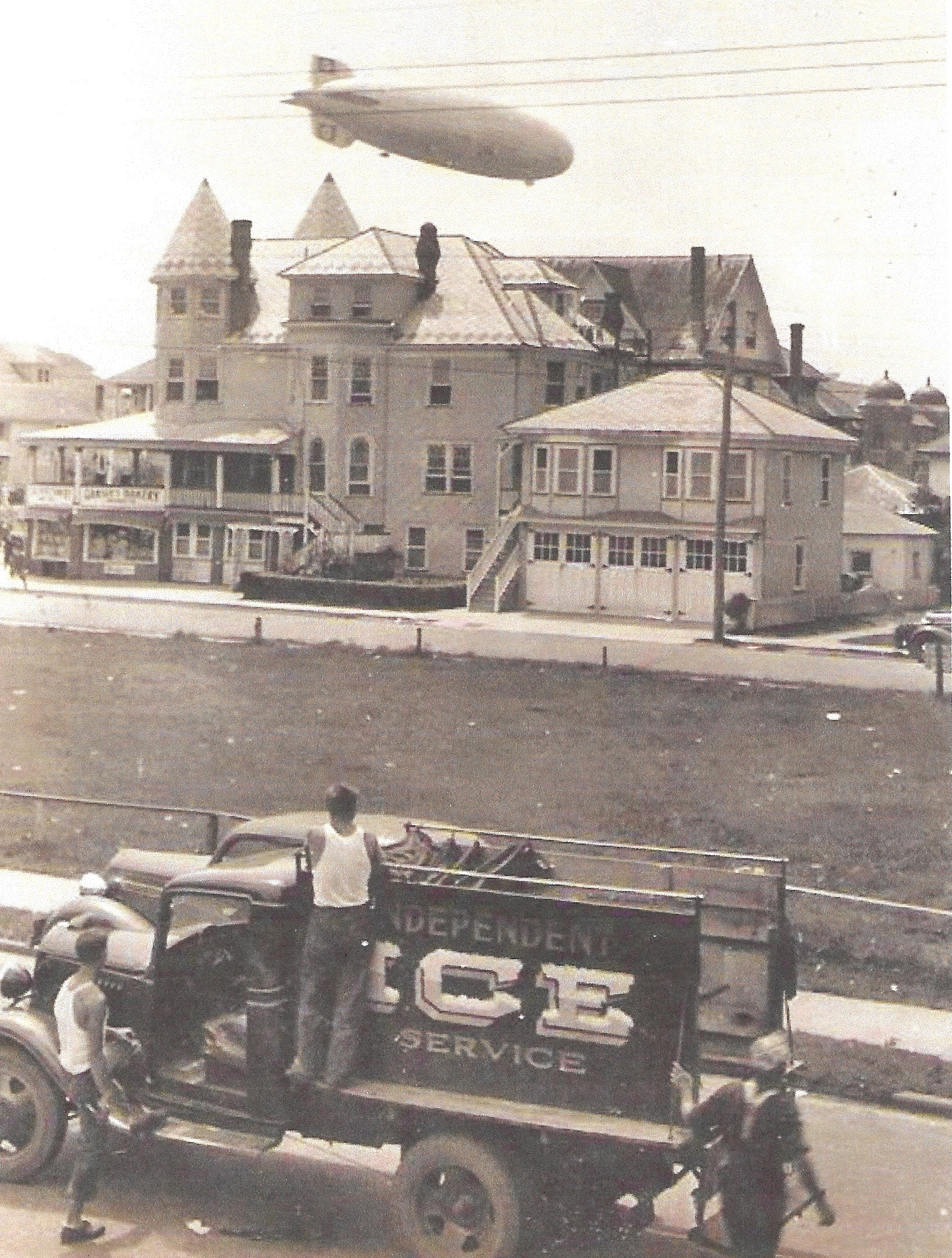

This photo captures the Hindenburg passing over the town of Wildwood, N.J. on that fateful day, May 6, 1937. Three young men standing on or by their truck are seen here looking up and observing the great airship overhead as it heads up the South Jersey coast to Lakehurst. Before long it would overfly Stone Harbor and Avalon as it progressed northward. Perhaps there even was a slight delay in the scheduled delivery of ice by the “Independent Ice Service” that afternoon. What an amazing sight this must have surely been for all who witnessed the Hindenburg that day.

Diridgable Hindenberg, Stone Harbor, NJ 1936

Shown here is yet another snapshot taken by an unknown photographer of the Hindenburg airship overflying Stone Harbor on the same day of May 6, 1937.

This particular photo image also resides in the Stone Harbor Museum archives and is being utilized with their permission.

As you can imagine, sightings of the Hindenburg created quite a spectacle and during this time the airship was seen and photographed at places like Wildwood, Stone Harbor, Tuckerton and surely many more South Jersey locations. This account includes a few photographs snapped by amateurs who happened to have a camera available to capture a very brief and fleeting moment in time of the silvery hull of the Hindenburg passing overhead. Little did anyone know the Hindenburg was about to make unthinkable and earth-shattering news.

Notice the 4 propeller driven engines powering the Hindenburg in this particular photo. These diesel engines could drive the airship at a maximum speed of 90 miles per hour mph with a standard cruising speed of 76 miles per hour.

When the communication from Lakehurst at 6:12 pm was radioed to the Hindenburg that conditions were suitable for landing, the airship was some 30 miles south and would spend another hour in the air in order to reach its destination. At 7:21 pm and approaching the mooring area at the Naval Air Station, the hovering Hindenburg initiated final preparations for landing by dropping its forward landing ropes to the ground below. And then, in just a blink of an eye, it happened!

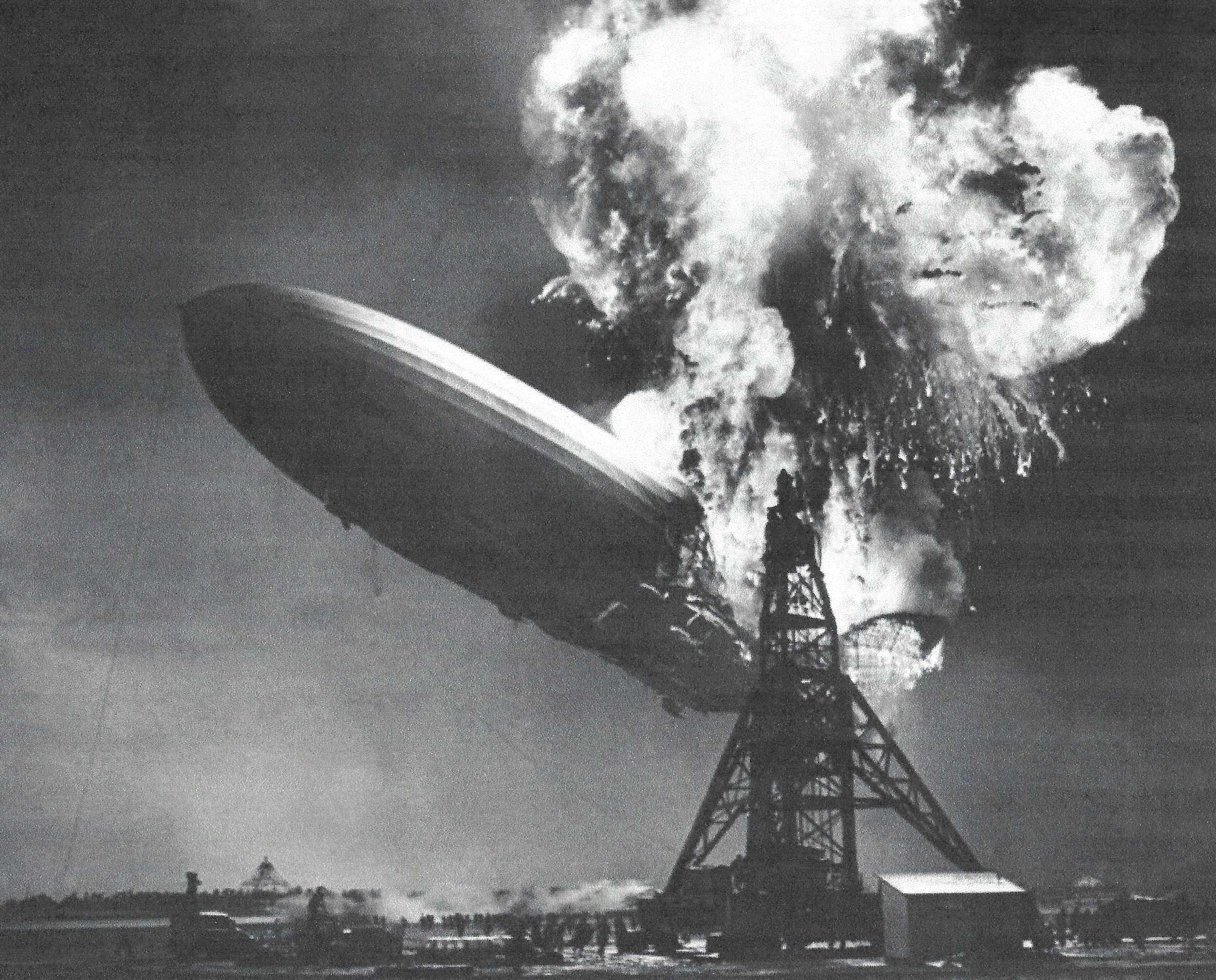

Here we see an all too familiar photograph taken at Lakehurst capturing the horrible moment when the explosion occurred that would prove to be one of the most recognizable and memorable images ever recorded in history! A news broadcast journalist and eyewitness assigned to cover the arrival of the Hindenburg memorialized the event when he recorded for posterity the following: “It burst into flames! . . . It’s burning, bursting into flames and it’s – and it’s falling onto the mooring mast and . . . this is terrible. This is one of the worst catastrophes in the world.”

THE TRAGEDY: The airship gracefully hung suspended about 75 feet above the airfield. Then at 7:25 pm there was a discernible “pop” followed by a brilliant flash with an explosion and a devastating fire enveloping and consuming the entire airship in a matter of 34 seconds.

Before anyone knew it, the great airship crashed to the ground and soon became a twisted mass of smoldering metal girders that once was the skeletal framework of the great airship. Unfortunately, when all was said and done, this catastrophe resulted in killing 13 of the 36 passengers, 22 of the 61 crew and a civilian member on the ground handling crew. Miraculously 62 of the 97 passengers and crew survived and seemingly surviving this inferno was mostly a matter of luck. Most assuredly, each survivor of this horrible incident had a story to tell and their personal accounts and observations were indeed riveting, captivating and useful. It can be said that all eyewitness accounts including survivors’ recollections would eventually become testimony for the various formal investigating proceedings and commissions conducted to determine the facts of this calamity.

Perhaps we will never fully know or understand what was the definitive cause of this tragedy. Please keep in mind that the airship contained 16 very large gas cells, each containing highly flammable hydrogen gas. Some believed that sabotage may have been involved. Others have maintained that perhaps a lightning strike is what caused this accident. Or just maybe the disaster was caused by an electrostatic discharge that ignited leaking hydrogen inside the cavernous fuselage. Numerous and more recent scientific inquiries have tended to support the latter idea that the build up of static electricity may very well have been the cause of this disaster.

In any event, what we do know is that this singular and tragic event brought to an abrupt end the age of the magnificent rigid airships and transcontinental passenger service.

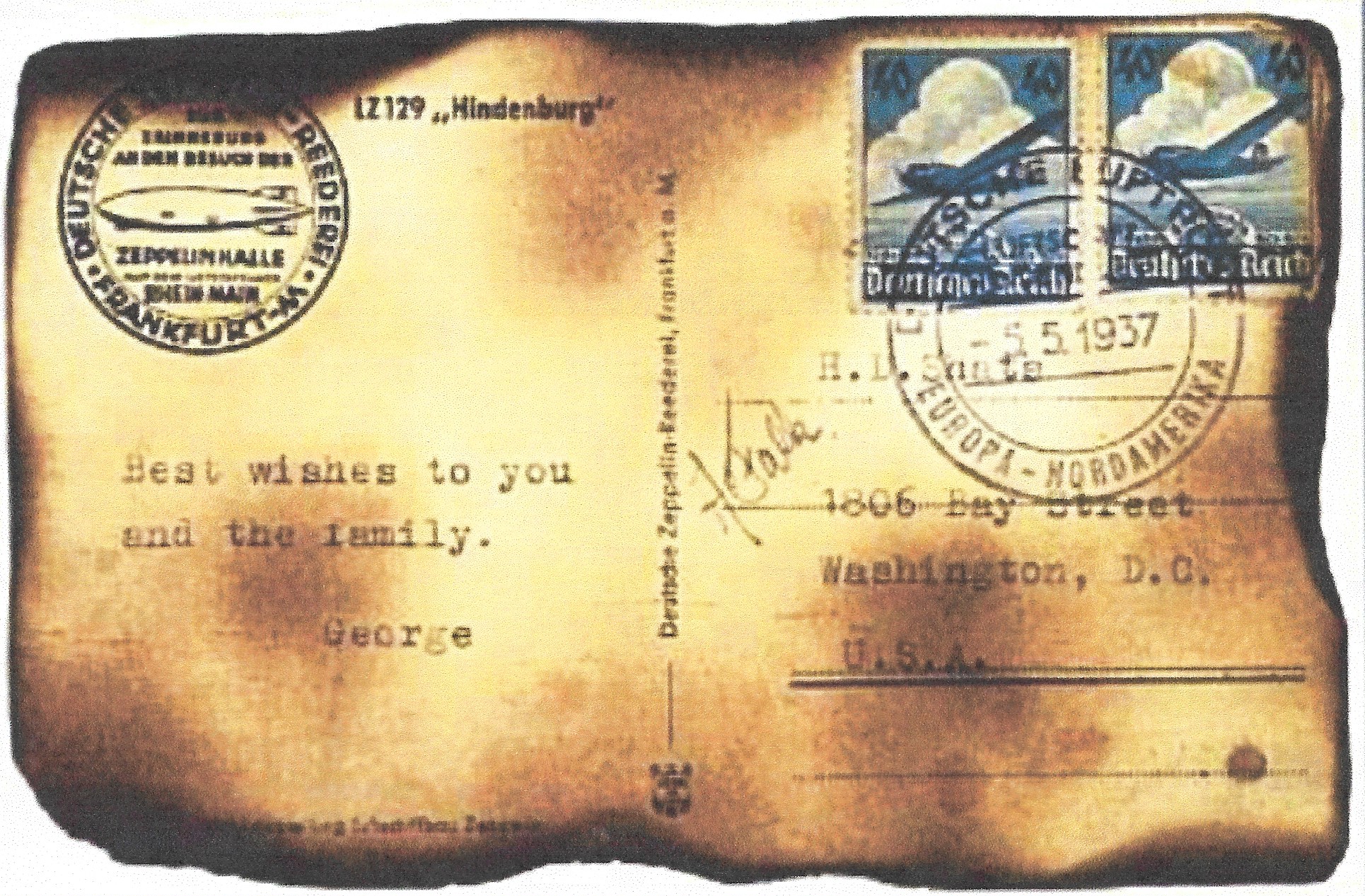

AN ACTUAL DISASTER AIRMAIL COVER: This last image shows an airmail flown post card that was actually salvaged from the Hindenburg wreck. Look closely for several key features. First we see the official postal marking/date stamp cancelling two German air mail postage stamps in the upper right corner of the post card. You may even be able to discern the postmark bears the date “ 5. 5. 1937” which is the European way of noting “5 May 1937”, the date this card was postmarked onboard the airship while enroute to the United States. That double-ring marking also contains the reference “EUROPA – NORDAMERIKA,” a special postmark used exclusively for mail dispatched over just this particular trans-Atlantic route. Next there is an imprinted, single-line inscription at the top left stating LZ 129 “Hindenburg”. In the upper left corner is a special philatelic inked imprint showing the outline or a design of the airship and designating that this mail was officially carried as “ZEPPELIN MAIL” from Frankfurt, Germany. All of these factors are important to documenting and proving that this particular post card was indeed actually carried on board the first flight of the 1937 season, May 5 to be exact, to North America. But, of greatest importance, we are immediately drawn to the most dramatic evidence of all – the burn markings around the outer edges of the card along with other scorched or singed brown areas affected by the extreme heat. Therefore, there is no doubt this very piece of mail was actually carried on the Hindenburg across the Atlantic Ocean to Lakehurst where it crashed and even endured – a testament to this horrific event!

A SIDE NOTE: One of the lesser known aspects that is associated with this story is that the Hindenburg actually had an official German post office on board which had authority to carry and convey mail and freight by offering rapid airmail transport at a time when steamships plied the oceans and took several days longer to transport mail and freight by surface methods. Two duly authorized Hindenburg crew members served as on-board postmasters and passengers as well as crew could purchase postage stamps, post cards and postal stationery for corresponding and mailing on board during their trip. The airship’s post room was a mere 6 feet square. Stamp collectors from all around the world were known to have air mail carried on board these transoceanic flights as a way to document the progress and developments of Zeppelin flights and have authentically flown Zeppelin mail for their stamp collections. During this short-lived era the German Zeppelins captured the imaginations and interest of so many people worldwide.

After the disaster of the Hindenburg, any surviving pieces of burnt mail recovered from the wreckage, mostly damaged, was discovered and processed by customs inspectors and postal officials for possible forwarding to addressees should sufficient contact information be available. Such pieces of “crash mail” from the Hindenburg have become sought after, highly collectible and are extremely valuable to those who collect such material. There were a total of 8 mail bags containing over 17,609 pieces of mail on board this very flight and it was reported by the U. S. Post Office Department that only about 2% of mail on board the Hindenburg that day actually survived without burn marks. In the end, approximately 163 pieces of mail were recovered subsequent to the crash at Lakehurst. Those very few recovered pieces of mail with decipherable addresses that were found were properly forwarded to their intended recipients. It is believed that only a portion of those recovered pieces of mail, perhaps half of them, have actually been accounted for although it is possible over time some more examples just might surface. But beware, because it was also reported that some unscrupulous persons or forgers have created “fake” crash covers and have tried to sell them at inflated prices to unsuspecting collectors.

CONCLUSION: There you have it! Another most interesting, albeit tragic, story tied to a single historic photograph unsuspectingly snapped by a resident in Stone Harbor, N. J. during the late afternoon of May 6, 1937. One just never knows the full story or meaning of some objects or even photographs like we have seen herein until circumstances intersect and create yet another story!

AUTHOR’S NOTE: It is my profound hope that readers will find this particular article to be both of great interest as well as highly informative.